I used to answer this question by saying “we started at different places, but the more that all of us are educated, the closer we tend to get to one another. These days there are probably more differences between practitioners in any of these professions than there are between the professions themselves.” Which is true.

I also used to say “I can’t talk about what they do, but I can tell you what I do”. Which is fair.

I’ve come to realise, though, that each of these professions has made important contributions to the field of manual therapy and, if you are interested enough to read a blog post on the subject, it is worth taking the time to talk about what these are.

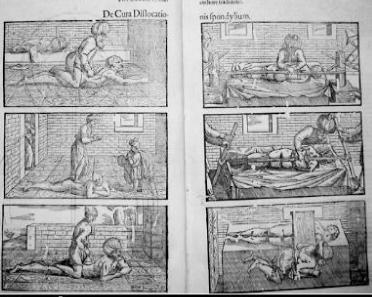

None of these disciplines “invented” manual therapy. It has been around for a long, long time. The medicine of most cultures has a form of it. There is a picture of manual therapy on the wall of “the physicians tomb” dating from about 2300BC in Egypt. Hippocrates, the “father of modern medicine” in ancient Greece, described a method for manually treating a back. (One person pulled on the head, a second pulled on the feet, and the third one jumped on the back. Brutal, but probably effective if the jumper new what he or she was doing.) The “Canon of Avicenna” from the Byzantine empire about 1000AD has a number of pictures of manual techniques.

None of these approaches invented “cracking joints”, either. That has been going on for a long, long time, in different parts of the world. There is an unbroken tradition of “bone setting” (as it used to be called) in parts of the world a least as widely spread as Russia, Iran, and Mongolia. AT Still, who “discovered” osteopathy in the late 1800s, was a bonesetter before he started calling himself an osteopath. But each of these disciplines has made important contributions to the field.

Contributions of osteopathy

1) The most important contribution of osteopathy is the way it thinks about health. This sets it apart, I believe, from just about every other approach to medicine, including other manual therapies. I wrote about this in my previous blog post (the short version in in the tagline at the bottom of this post; and in particular, the part about connections throughout the body). Understanding the way that the human body connects with itself in health is, I think, an area where modern medicine has to some extent lost its way, and where osteopathy has a real contribution to make. I’ll write about this more in later posts.

2) Osteopaths have developed a huge range of techniques, from the very subtle and gentle to the quite physical. This makes it useful for all sorts of people. Many of the techniques it has developed have been picked up by other therapists, who find them good enough to use as a modality on their own. Examples of the gentle techniques are osteopathy in the cranial field, which has been picked up by others as “cranio-sacral therapy” and counterstrain (which is becoming increasingly widely used). Examples of more physical techniques are muscle-energy technique, which have been picked up by physiotherapists as “PNF stretches”, (although physiotherapists don’t usually use them in a targeted, precise way to help specific joints to move) and treatment of the lymphatic system, which has been picked up and widely used as “lymphatic drainage massage” (although that is usually used for a narrower range of conditions than osteopaths use it to treat). Again, I will write more about this in later posts.

3) Osteopathy has, in many ways, always been ahead of its time. That’s a big call, but it’s also historically verifiable.

|

Over 100 years ago, AT Still said… |

Much more recently, others have said… |

|

“We strike at the source of life and death when we go to the lymphatics” |

“This paradigm shift simultaneously forced us to take a brand-new look at the lymphatic system as the other, not the secondary, vascular system. Considering the vital functions that the lymphatic system engages in and how little knowledge we have regarding the system, lymphatic research is truly a gold mine that invites ambitious young scientists and clinicians.” (Choi I, Lee S, Hong YK 2012 The new era of the lymphatic system: no longer secondary to the blood vascular system. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med Apr;2(4):a006445) |

|

“The mechanicalprinciples on which osteopathy is based are as old as the universe.” |

“There has been a renaissance in the field of mechanobiology over the past two decades. Physiologists and clinicians now recognize the importance of mechanical forces for the development and function of the heart and lung, the growth of skin and muscle, the maintenance of cartilage and bone, and the etiology of many debilitating diseases….At the same time, biologists have come to recognize that mechanical forces serve as important regulators at the cell and molecular levels, and that they are equally potent as chemical cues.” (Ingber DE, 2003 Mechanobiology and diseases of mechanotransduction Ann Med 35: 564-577) |

|

“I know of no part of the body that equals the fasciaas a hunting ground.” |

“Studying fascia objectively at the basic science and clinical levels will provide important information that may change clinical practice. Once the structure and functions of fascia in the musculoskeletal system are further elucidated, the pathophysiology of many disorders and their consequences may be better explained. Many neuromuscular and musculoskeletal disorders can be additionally served by research with a fascial perspective in order to optimize treatment strategies.” (Kwong EH, Findley TW. 2014 Fascia–Current knowledge and future directions in physiatry: narrative review. J Rehabil Res Dev 51(6):875-84) |

John Smartt Osteopath Bachelor of Applied Science (Osteopathy) Master of Osteopathy (UWS)

e: info@smarttosteopath.com p: 0409-777-604 a: SYDNEY CITY: Suite 12, Level 10, The Dymocks Building, 428 George St Sydney, NSW 2000 (City on-line bookings): Thu, Fri a: MORTDALE: Mortdale Allied Health, Shop 1, 118 Railway Pde, Mortdale, NSW 2223 (Mortdale on-line bookings): Sat, Sun a: EDGECLIFF: Genbiome, Suite 2, 2 New McLean St Edgecliff, NSW 2027(Genbiome on-line bookings): Wed

Contributions of chiropractic

While osteopaths have thought about finding the cause of ill health, the genesis of chiropractic, about 10 years after osteopathy (in 1895), was based on the idea that the founder largely knew what the cause of ill health was: the spine and the nervous system. It would be easy to be dismissive of the contribution that chiropractic has made, for this reason. However, chiropractors of various schools have added their own really interesting innovations. At least two areas (and quite possibly more) have, I believe, made a massive contribution, and will probably make bigger ones in the future.

1) Through their emphasise the importance of the nervous system, chiropractors are now leading the way in a hugely exciting field of medicine called (in the US) “functional neurology” (no one is quite sure what to call it in Australia). This approach involves a very indepth understanding of the anatomy of the nervous system, and a range of neurological testing, to work out just what parts of a patient’s central nervous system are struggling. It then uses the “plasticity” of the nervous system to use exercises to improve the functioning of the parts of the brain that are struggling. Chiropractors aren’t the only people doing this work, but they seem to be leading the way.

2) A related but separate area, which has also grown out of chiropractic, is “applied kinesiology“. The scientific basis for this isn’t as clearly understood as the basis for functional neurology, but it is capable of delivering some amazing results. I use two approaches that are derived from it: “Neuro Emotional Technique” (NET) and the “Neurological Integration System” (NIS, or “Neurolink” (which was developed by an osteopath, but largely owes its basis to applied kinesiology).

Chiropractors have come under a lot of criticism over the years. Initially, that largely came from osteopaths, who accused them of using a bastardised form of osteopathy without adequate training. They have, though, done some very cool work, and they deserve the credit for it.

Contributions of Physiotherapy

1) Physiotherapy has always been about exercise, and getting things moving generally. It can trace its origins to the Swedish Gymnastics movement from the early 1800s. This was mostly about trying to generally get the population more physically fit, for military purposes. It included manual therapy, and particularly massage (although European massage is older than this, and “Swedish massage” is actually more of an American concept than a Swedish one). Phystiotherapy was used early in the 1900s with polio victims, the emphasis being simply on getting them moving. By emphasising the activity of the patient within manual therapy, physiotherapy has made a great contribution to the field, and most manual therapists now probably recommend some sort of exercise activity to supplement what happens in the treatment room. (I use all sorts, as appropriate, but two approaches I particularly like are “Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilisation” (DNS) and “Trauma Release Exercises” (TRE)). I personally believe that the degree of scientific evidence for prescribing specific exercises for specific conditions is much more limited than is often believed (although the evidence for exercise generally is pretty solid); particularly compared to the evidence for osteopathic treatment, and treatments developed by osteopaths. There tends to be an assumption in our society that exercise will always be beneficial, and so the actual science behind it doesn’t always get scrutinised as closely as it probably should. Never-the-less, exercise can be really important, and we have physiotherapists to thank for promoting it.

2) During the late 1800s and early 1900s, physiotherapy was largely adopted by nurses who did some extra training. For this reason it has always been an accepted part of mainstream medicine, whereas osteopathic and chiropractic were started from “outside the tent”, and have a history of being “alternative”. I would argue that, whether by clever design or simply cultural norms, physiotherapists have largely achieved and maintained this position by not trampling on the turf of doctors. So, for example, they have always done work post operatively, but virtually never pre-operatively. They have tended to stay away from anything to do with the abdominal organs, and anything that suggests they could do anything to equip people’s bodies to be better at dealing with pathogens. It is unfortunate that, because this has been their position, and because they are a large and successful profession, others have sometimes believed that the limitations they have placed on themselves have a scientific basis; which they most certainly do not. It is no small achievement, though, for manual therapists to be accepted by mainstream medicine. Hostility from mainstream medicine to manual therapy pre-dates the foundations of osteopathy, and goes back at least to the time of bone setters. The world would definitely be a better place if osteopathy was as well-accepted by mainstream medicine as physiotherapy has managed to be.

After having my interest in manual therapy and massage triggered by a trainee physiotherapist, and being treated for years by a very good chiropractor, I decided to invest five years of my life studying osteopathy. Clearly I personally think that it is the best approach, with the most coherent rationale and the most comprehensive set of techniques. But none of us can afford to be arrogant; there is too much for all of us still to learn. We have learned a lot from one another, and can certainly continue to learn more.

“Let us not be governed today by what we did yesterday, nor tomorrow by what we do today, for day by day we must show progress.” AT Still